By Caroline Savoie

A plaque stands in front of the building that once housed the Black Cat bar, Leslie Cochran’s main haunt, 11 years after his death.

“Leslie, Queen of Austin (born Albert Leslie Cochran), roamed 6th St. in g-strings and heels with his trademark goatee, and had a saucy comment for every passerby who snapped a photo with him,” the plaque reads, reminding locals and tourists of the character who once stood there.

As executive director of Austin’s street association at the time of Cochran’s death in March 2012, his friend Debbie Russell oversaw the project.

“It was the least the city could do for him,” Russell said.

Along with the plaque, Russell called on her community organizing skills to plan a parade the week after Cochran’s death. She said Austin Police Department officers held an escort from Cochran’s cemetery plot, some even marching in the parade on foot, as Cochran’s sister Alice led the parade.

Through Love for Leslie, a Facebook page Cochran’s “personal secretary” Valerie Romness set up to share the status of his condition, the public knew when and where to meet after his death.

“I’d been preparing the public to march after his death, and hundreds of people showed up,” she said. “People were joining in as we were marching down Sixth Street.”

Cochran’s burial plot was donated by Garden of Risen Christ, and his final resting place lies among the gravesites of “priests and babies,” Romness said.

In 2010, nearly 20 years after director and producer Tracy Fraizer first saw Cochran “in the wild,” she met Ruby Martin, one of Cochran’s friends, hairdressers, and the main source for footage of Cochran over the years.

“I just so happened to walk into a salon and sat in Ruby’s chair,” Frazier said. “She said working on a documentary on Leslie, and I asked her if I could help. She showed me a lot of the early footage that she captured of him; it started in 1996.”

Frazier said she’d worked in film before, and she was missing that aspect of her life. Martin mentioned that she’d been filming Cochran for a documentary-style project called American Drifter, and she shared her footage with Fraizer as part of a long-form documentary that would premiere at SXSW a decade after that salon chair conversation.

“With her footage, she was able to be real with him,” Fraizer said. “It was the most unaffected footage I’d seen. He’s usually posing or playing to the camera, but with her, he was just himself.”

The first time Frazier saw Cochran, she was on a bus on the way to the gym in the early 1990s. Frazier said all of a sudden, people started getting up from their seats and looking out the windows on the side of the bus closest to the sidewalk, where Cochran was walking.

She said he was unlike anyone she’d ever seen before. Frazier said the bus patrons looked around at each other and smiled once the bus had passed Cochran by.

“He brought everyone together for just a second,” Frazier said. “He was like the most unusual lion tamer in the circus, where he’d bring you into his world with his energy and theatrics. He was like a lion-tamer at a really freaky circus, and we were all of his lions. He could work a crowd and connect with people unlike anyone I’ve ever met before or since.”

While Cochran never openly identified as queer, his friends and fans alike say that he embodied the word.

“Before the word ‘genderfluid’ existed in our vocabulary, he taught me what it meant,” Frazier said. “It depended on the day, what pronouns people would use for Leslie. Leslie was just Leslie.”

Romness shared a similar sentiment.

“He taught me how to be myself,” she said. “I grew up as a tomboy, and I like being a girl, but I don’t like asking men for help or dressing really feminine. Dressing like Leslie taught me how to show just enough femininity that felt real to me.”

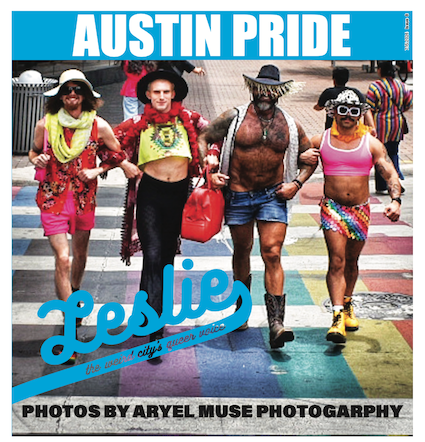

Before and since his death, Cochran’s friends pay homage by dressing up in his favorite gear: stockings, heels, miniskirts, g-strings, crop tops, hats and wild hair.

“I used to think there was no way I could impersonate Leslie because I don’t have the balls,” Romness said. “So I have to use a pair of socks.”

Frazier’s production company, Freckled Fanny Films, wanted to premiere Becoming Leslie before Cochran’s death to show the beloved, adopted Austinite what he meant to the city.

“He would have absolutely loved to go to his own movie,” Frazier said. “At the end [of the movie], when he talks about how Austin isn’t Austin anymore, it made us want to show him that people still loved him. I wish he would have seen it.”

She said she didn’t want to focus on his pronouns or performative nature, but instead, she wanted to get to the heart of the man, and that included sharing “the hard stuff.”

“Between the trauma and brain injuries and self-medicating on top of getting older, Leslie was an unreliable narrator, and his memories were blurry,” she said.

Romness said Cochran could offer people complete understanding and acceptance without judgment because of his own traumas and mistakes.

“You don’t find many people who care for you unconditionally,” she said. “That’s why I don’t hold back on any of the ugly stories about Leslie, because he was a whole person with different sides of himself.”

Romness said that for as brave, wild and just Cochran was, he could also be selfish, disrespectful and stubborn.

To fill in some gaps in Cochran’s backstory, Frazier interviewed his sister Alice after he died to understand what it was like to grow up in 1950s Miami. She learned more about his abusive childhood and confirmed that Cochran did in fact have a twin who died in utero before his birth, who his mother convinced Cochran he killed.

“Making the movie took a lot of emotional energy out of me,” Fraizer said. “But when we screened it at South By Southwest in 2019, and I saw his friends and family come out to support the movie, I knew it was worth every second.”

On June 24, 2012, what would have been Cochran’s 61st birthday, Brently Heilbron organized the first Leslie Fest to commemorate the Austin icon. While the event wasn’t recreated for years, a young Austin real estate agent and community organizer, Andrew Griffin, decided to bring Leslie Fest back.

Griffin said that he first learned about Cochran during the COVID-19 pandemic, and he became obsessed.

“I really loved how beloved he was by the entire community, from being a street icon to running for mayor,” Griffin said. “I kept seeing things in Austin get bulldozed that had the potential to be iconic gay murals and historical sites. Leslie was an icon for queerdos like Marsha P. Johnson was for trans folks, this person we could raise up and put in public view for perpetuity.”

Griffin said he was sitting on his relatives’ front porch one day talking about how Cochran needed to be remembered. One of the relatives pulled out his phone and showed him a picture of the two men with Cochran, one of whom was Bob Baird, one of Cochran’s lawyers and closest friends.

“I had no idea they knew Leslie,” Griffin said. “It felt like kismet, that moment, and it was just a week before Becoming Leslie premiered at the Blue Starlight theater.”

Griffin said he met Cochran’s motley crew at the premiere and chatted with Romness about bringing Cochran’s beloved memory back into Austin.

“The events in his memory were being less and less attended, so I really wanted to boost promotion for any events in Leslie’s name,” Griffin said.

Griffin said he’d always heard that Austin was safe for and celebrated weirdos, but he said he hasn’t found that to be the case. He said when he moved from Chicago to Austin in 2020, people were not opening up their bubbles to outsiders, and it took lots of time and concerted efforts to find his group of people.

“I feel like through Leslie Fest, Leslie Day and other efforts, I’m trying to keep Austin weird, so the queer, weird, strangeness can never leave, no matter what the population looks like,” he said. “Many of Austin’s LGBTQ+ elders want to stay in Austin after retirement, but they’re getting priced out. I mean hell, even the slogan ‘keep Austin weird,’ has been bought.”

Griffin said in 2022, 15 people attended the Leslie Fest event he organized on Cochran’s birthday. He said in 2024, he’s planning events for Leslie Day on March 8, Queer Bomb, Austin’s alternative Pride festival, on June 1, and Leslie Fest on June 20.

He said that the events will all send proceeds to local LGBTQ+ and animal charities, as Cochran loved people and pets with similar fervor. He said transgender and intersex folks are slated to speak at the Leslie Day event.

Cochran didn’t have the language during his life to talk about how he presented, and his friends speculate about how he would identify in 2023, both sexually and in terms of gender.

“He presented however he wanted to present,” Griffin said. “It got him a lot of attention, and it got him arrested, but he stayed true to himself to present how he felt comfortable. He would absolutely be in support of drag queens and self expression, but we can’t speculate on how he would identify. We can ensure that the things he supported and believed in are supported through these movements.”

Frazier said that in the four years since Becoming Leslie premiered, she’s been pleased to learn that the film opened up a conversation around mental health, sense of belonging, and what home really means.

“He was a reminder not to take yourself so seriously and be yourself in public,” she said. “People used to point to him and say Leslie was their beacon of hope to be who they want to be. He was a lesson in acceptance over and over again.”

Romness said the Love for Leslie Facebook page is still going strong with nearly 900 members. She said new people are still joining the group, perhaps brought to the page through their own journey learning about Cochran’s impact.

“Asking what’s your favorite thing about Leslie is like asking what’s your favorite song in the world,” Russell said. “There’s too many. For as many fuck-ups he made and boundaries he crossed and bridges he burned, Leslie was respectful and generous and kind. He was our friend.”